Public health authorities all have the same message for you right now: If you don’t want to get coronavirus, stay home, and wash your hands. Hand sanitizer, so long as at least 60% alcohol, is offered as a backup to hand-washing. [CDC] [WHO]. What’s going on here? Why is a product with “sanitize” in the name playing second fiddle to soap and water? Because, as we’ll discuss today, soap doesn’t just wash coronaviruses off your hands. It destroys them using thermodynamics.

Article by Rachel Jones, Little Shop of Physics Science Writer (rrjones@rams.colostate.edu)

The take-home message

When viruses are floating about in the world, the genetic material that allows the virus to really cause trouble inside human cells is surrounded by a protective covering. In SARS-CoV-2 viruses, this coating is made of special lipid molecules. It costs less energy for the molecules in this coating to be close to each other than it does for them to be close to water molecules. This means that the molecules in the coating stick to each other really well in watery environments (such as the respiratory droplets people produce when coughing or sneezing).

However, because of their structure, soap molecules can work their way between the virus’ lipid coating molecules and reduce the energy cost of being close to water molecules. This process essentially dissolves the virus’ protective layer. When the virus is broken down this way, it is no longer infectious — it can’t make you sick. However, it’s important to remember that the coronavirus also spreads via respiratory droplets in the air, and transferring viruses to your face when you touch it with unwashed hands certainly isn’t the only way — or even the primary way — you could be infected.

So, stay home whenever you can. And when you can’t stay home, wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds whenever you can. You’re not sending coronaviruses down the drain — you are breaking apart their protective shields at the molecular level. (But if you can’t wash your hands, do use hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol; early research results suggest that this is effective against the coronavirus.)

The deep dive

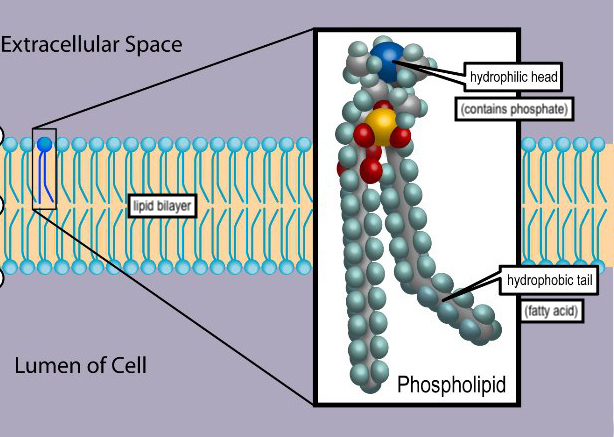

To the best of our current scientific understanding, the SARS-CoV-2 virion is surrounded by a lipid bilayer, much as your cells are — in fact, SARS-CoV-2 virions take the molecules to make their lipid bilayers from the cells they infect [1]. In biochemical terms, the molecules in a lipid bilayer are amphipathic [2]: They have a segment that is attracted to water (hydrophilic) and a segment that repels water (hydrophobic). These molecules are typically phospholipids. In a phospholipid, the hydrophilic heads contains phosphate and faces the watery insides and outsides of cells; the hydrophobic “tails” are two fatty acid chains which situate themselves in the interior of the bilayer. A typical phospholipid is diagrammed in Figure i. Now, what, you may ask, makes a molecular structure hydrophilic or hydrophobic? This is a good question, and one that is relevant to understanding the efficacy of soap against SARS-CoV-2.

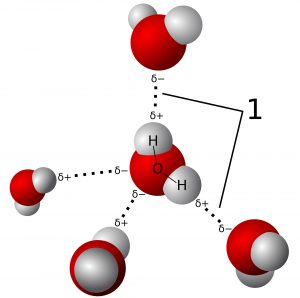

To answer this question, we’ll first answer another: Why is water wet? This is because of hydrogen bonding [2]. Hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) occur between (as you’d expect) a hydrogen atom carrying a partial positive charge (symbolized 𝛿+) and some other atom carrying a partial negative charge (𝛿-). When a molecule has some regions that are 𝛿+ and some that are 𝛿-, we say the molecule is polar. Water molecules (chemical formula H2O) are polar: the hydrogen (H) atoms are 𝛿+ and the oxygen (O) atoms are 𝛿-, so H-bonding occurs between H and O atoms of neighboring molecules (illustrated in Figure ii). This bonding makes water molecules tend to stick together, though H-bonds can be easily broken and re-formed between different molecules. The formation of H-bonds is energetically favorable — it brings molecules to a lower-energy state [2].

Now, to hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity. Polar molecules (or polar regions of molecules) can also form H-bonds with water molecules. The phosphate-containing “head” of a phospholipid is polar, so water molecules can readily form, break, and re-form H-bonds with this portion of the molecule just as they would with other water molecules. There isn’t an appreciable energetic cost to polar groups, such as the “head” of a phospholipid, hanging out with water molecules, so these groups are hydrophilic [2]. To explain hydrophobicity, we’ll need to consider a concept from thermodynamics: entropy.

For our purposes, it is sufficient to think of entropy primarily as disorder and randomness, and to know that, according to the second law of thermodynamics, the entropy of the universe must always increase. Decreasing entropy — imposing order — requires the input of energy (and the provision of this energy ultimately increases the entropy of the universe, keeping things thermodynamically sound). To bring this all together: Hydrophobic molecular structures are non-polar — they cannot form hydrogen bonds with water molecules. Because of this, water molecules are forced to bond with one another in very particular, structured ways near a hydrophobic region of a molecule, forming a “cage” or “shell” around it [2]. The formation of structure in this way decreases entropy, which requires energy and thus is thermodynamically disfavored. However, the overall decrease in entropy can be limited if hydrophobic regions of molecules pack in close to one another, limiting the number of water molecules that must form cages [2]. Ultimately, in the case of phospholipids, this drives the formation of lipid bilayers (refer again to Figure i).

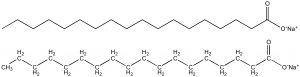

And now, finally, we can answer the question we started with: Why does soap work? This hinges on the fact that soap molecules look and behave quite a bit like phospholipids. Soap molecules have a polar head, but just one fatty acid tail (refer to Figure iii). Because the hydrophilic heads of these molecules are wider than their hydrophobic tails, when they’re in a watery environment they tend to form spherical structures called micelles rather than lipid bilayers [2]. In a micelle, the hydrophobic tails are packed together in the interior of the sphere and the hydrophilic heads face the watery world beyond. Micelles are important for our purposes because they can trap hydrophobic regions of other molecules in their interiors, thus eliminating any entropic benefit of these regions being located within a lipid bilayer [2].

We have good evidence that the lipid bilayer and the proteins associated with it are essential for SARS-CoV, the closest relative of SARS-CoV-2 that we’re aware of, to invade host cells [3], which any virus must do to cause disease. Therefore, disrupting the viral lipid bilayer, as you do with soap, should be highly effective in deactivating virions on your hands. And indeed, evidence suggests that properly washing with soap and water dramatically reduces the quantity of infectious H1N1 influenza virions (which also have lipid bilayer coats) present on skin, even more so than alcohol-based hand sanitizer does [4]. However, it’s important to note a number of caveats here, and not rely solely on good hand hygiene to protect you from COVID-19. One meta-analysis suggests that washing your hands can help protect you from respiratory illnesses, but as a single strategy it certainly won’t prevent all — or even most — respiratory infections [5]. At the time of writing, social distancing and good respiratory hygiene (covering your cough or sneeze with a tissue or the inside of your elbow) are still essential to reducing your risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and slowing the spread of COVID-19.

Stay home. And when you can’t stay home, wield the power of thermodynamics as often as possible: Wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds.

(And a final note: Preliminary evidence does support the idea that, as health agencies suggest, proper use of a hand sanitizer containing at least 60% alcohol could inactivate SARS-CoV-2 [6]. If you can’t wash your hands with soap and water, use such products. But please don’t hoard them.)

References

[1] Liu C, Yang Y, Gao Y, Shen C, Ju B, Liu C, Tang X, Wei J, Ma X, Liu W, Xu S, Liu Y, Yuan J, Wu J, Liu Z, Zhang Z, Wang P, Liu L. Viral architecture of SARS-CoV-2 with post-fusion spike revealed by cryo-EM. Preprint posted 5 March 2020 to bioRxiv. Available from https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.02.972927

[2] Nelson DL, Cox MM. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry (6e). New York (NY): W. H. Freeman and Company; 2013. 1198 p.

[3] Millet JK, Whittaker GR. 2018. Physiological and molecular triggers for SARS-CoV membrane fusion and entry into host cells. Virology 517: 3-8. Available from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2017.12.015

[4] Grayson ML, Melvani S, Druce J, Barr IG, Ballard SA, Johnson PDR, Mastorakos T, Birch C. 2009. Efficacy of soap and water and alcohol-based hand-rub preparations against live H1N1 influenza virus on the hands of human volunteers. Clinical Infectious Diseases 48: 285-291. Available from https://doi.org/10.1086/595845

[5] Aiello AE, Coulborn RM, Perez V, Larson EL. 2008. American Journal of Public Health 98: 1372-1381. Available from https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.124610

[6] Kratzel A, Todt D, V’kovski P, Steiner S, Gultom ML, Thi Nhu Thao T, Ebert N, Holwerda M, Steinmann J, Niemeyer D, Dijkman R, Kampf G, Drosten C, Steinmann E, Thiel V, Pfaender S. Efficient inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 by WHO-recommended hand rub formulations and alcohols. Preprint posted 17 March 2020 to bioRxiv. Available from https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.10.986711

Image credits

[i] “Phospholipid” by By Superscience71421 – own work. Used under CC BY-SA 4.0. Available from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=53649846 / Information about chemical composition of diagram components added

[ii] “Model of hydrogen bonds (1) between molecules of water” by User Qwerter at Czech wikipedia: Qwerter. Transferred from cs.wikipedia to Commons by sevela.p. Translated to english by by Michal Maňas (User:snek01). Vectorized by Magasjukur2 – File:3D model hydrogen bonds in water.jpg. Used under CC BY-SA 3.0. Available from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14929959

[iii] “Two images of the chemical structure of sodium stearate, the main ingredient in soaps”, by Smokefoot – own work. Used under CC BY-SA 3.0. Available from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20293318